How to Read Swedish Household Examination Records (Husförhörslängder) for Genealogy

Save this to Pinterest!

The Swedish Household Examination Records, or Husförhörslängder, are the go-to records for Swedish genealogy (you can read more about them in the previous blog post, Household Examination Records for Swedish Genealogy). If you are just beginning your Swedish genealogy research, getting started with Household Examination Records can be a daunting task - especially if you don’t know any Swedish! But fear not, once you have a basic understanding of how to read a page and what to look for, you’ll soon master this record set. In this blog post I’ll walk you through the main sections on each page of the Household Examination Records and what to look for.

It is important to note that the page designs of the records change depending on what year they were taken: a record from 1870 will look different than record from 1840, but there is basic information that is covered in each of them - it may just be presented differently.

Note also that this blog post will only cover genealogically-relevant information in these records. It will not go over the religious notes that you can also find in the Household Examination Records, and for which the record-keeping was actually meant.

1. Location

The first thing you’ll notice on any given page is a string of Swedish words at the top: this is a location! More specifically, this is the farm or village within the parish. The parish is indicated by the book itself: Household Examination Records were taken parish by parish, and the parish name is on the book. If you are a little confused about Swedish land divisions (county vs. parish vs. rote vs. farm) you should read this blog post: Understanding Swedish Land Divisions for Genealogy.

Here is an example:

Though a little difficult to read, this page lists households who lived in Qvanslof Norregard, which is written at the top of the page next to page number 146. This was the specific location within the parish of Ljungby, and we know that because this page is actually from the Ljungby Husförhörslängder - remember, every parish had their own books.

2. Names

Much like U.S. censuses, the first column of each page contains the names of each person living in the household. You might notice some abbreviated words before a name: maybe “eg”, short for egare, which means owner, or “pig”, short for piga which means maid/spinster/single woman. You’ll probably notice a lot of “h” next to women on the pages - this is short for hustru or wife. You’ll undoubtedly see a lot of “s” and “d” short for son and dotter - indicating the gender of each of the children. Before you even get to the names, these abbreviations can tell you a lot about a person, so don’t ignore them! Book mark this FamilySearch Wiki page which contains a list of all the abbreviations you might come across: Swedish Abbreviations in Family History Sources.

From the same page as above, this example shows all the names in the household of Peter Andersson. It shows ‘inh’ next to Peter’s name, which is short for the Swedish word inhyses meaning lodger - this makes sense, because above Peter’s name you can see the name Johan Gustaf Andersson, next to the abbreviation ‘eger’ for egare, owner.

Next to Lena Cajsa Svensdotter, you see “h” short for hustru indicating she is the wife of Peter, and the names that follow either have “d” or “s” preceding them, indicating whether they were a son or daughter.

Here it is important to note also that women retained their maiden names; note that Lena Cajsa is not written as “Lena Cajsa Andersson” because she is married to Peter Andersson, but rather she retains her maiden name of Svensdotter.

You might also be wondering why the names are crossed out. This was done when a family moved out, to indicate they no longer lived in that place anymore. This is explained in more detail below.

3. Date and Place of Birth

This is where the Household Examination Records start to get juicy. Unlike U.S. censuses which only record the year a person was born (and oftentimes it was an estimate), these record sets recorded the exact year, month, and date. Under the ‘birth’ section, which may be written as Födelse or Född in earlier records, it will give the year and the date written as day/month (not month/day - remember, these aren’t American records!). Newer records will also show the place of birth, which is in reference to the parish. If no place is given and the column is left blank, that typically means that the person was born in the same parish as the page you’re looking at.

Here’s an example from the same page above:

This shows the Födelse column with sub columns asking for år (year), mån och dag (month and day) and ort (place). It shows Peter Andersson was born October 6, 1817 in Pjätteryd, and Lena Cajsa Svensdotter was born June 5, 1841 in Kånna. The eldest daughter, Ingrid Catharina, does not have a place listed for her, indicating she was born in the same parish as this book.

Here is an example of what this column may look like from a much earlier record, taken in 1820. This record actually shows Peter, or Petter, as a young child living with his parents, Anders Persson and Svenborg Jonasdotter, and the rest of his siblings. Note the column title is Född and only dates are given with no attention given to places.

But, also note that the birth date given here for Petter, October 6, 1817, matches exactly to that given in the later record above. Swedish record keeping was amazingly accurate!

4. Marriage Date (and Death Date)

Marriages were recorded in Household Examination Records beginning in 1861, when the page added a column for Äktenskap, or marriage. This column will show the date of marriage under Gift (married) and also the date either the husband or wife became a widow if their partner died (under ‘enkl eller enka’, short for enkling eller enka, widow or widower). This date will provide you with a date of death, which may also be provided under a separate column, Död, depending on the year of the record you’re looking at.

Here is an interesting example:

This page shows the same Peter Andersson that we discussed above, and it actually shows two wives under him (indicated by the “h” meaning hustru or wife). Anna Stina Svensdotter, his first wife, died on June 2, 1861 as indicated in the far right column, Död. Her death is also indicated by the fact that her name is crossed out. Under the Äktenskap column, it shows that Peter then married his second (significantly younger) wife Lena Cajsa Svensdotter on May 3, 1863. When she joined the family, her name was squeezed in between Peter and Anna’s names; the record keepers made do with limited page space.

5. Arrival and Departure

This information is the best part of Swedish Household Examination Records: this is the information that will help you trace your Swedish ancestry back generations. These records recorded when a family arrived in the parish or specific village/farm where they lived within that parish, when they left, and where they left to. So, with this information, you can see how it becomes possible to trace people forward and backward in the books! The information is portrayed a bit differently depending on the year of the record you are looking at.

In earlier books (books prior to 1861) there will be a column entitled Flyttningar which means relocations. This column will be divided into sections for från (from) and till (to) and, depending on the year, might also have separate subcolumns for år (year).

After 1861, the records divide the relocations column into flyttad från (coming from) and flyttat till (going to), with the latter being the last column of the record, all the way on the right hand side.

Regardless of how the columns are presented, the information under them will be portrayed the same way. It will show a year, month and day, allowing you to know exactly when your ancestors arrived and when they left any given place. It will also show either a page number or say the name of a place. The place is the name of the parish your ancestor came from or went to, indicating that you’ll find them in a separate book when you either trace them back or forward (remember, every parish had its own book). If it has a page number, it means your ancestor lived in the same parish, but in a different village/farm, indicated by the page number given. So to trace them, you stay in the same book and just flip to that page number.

Let’s look at some examples.

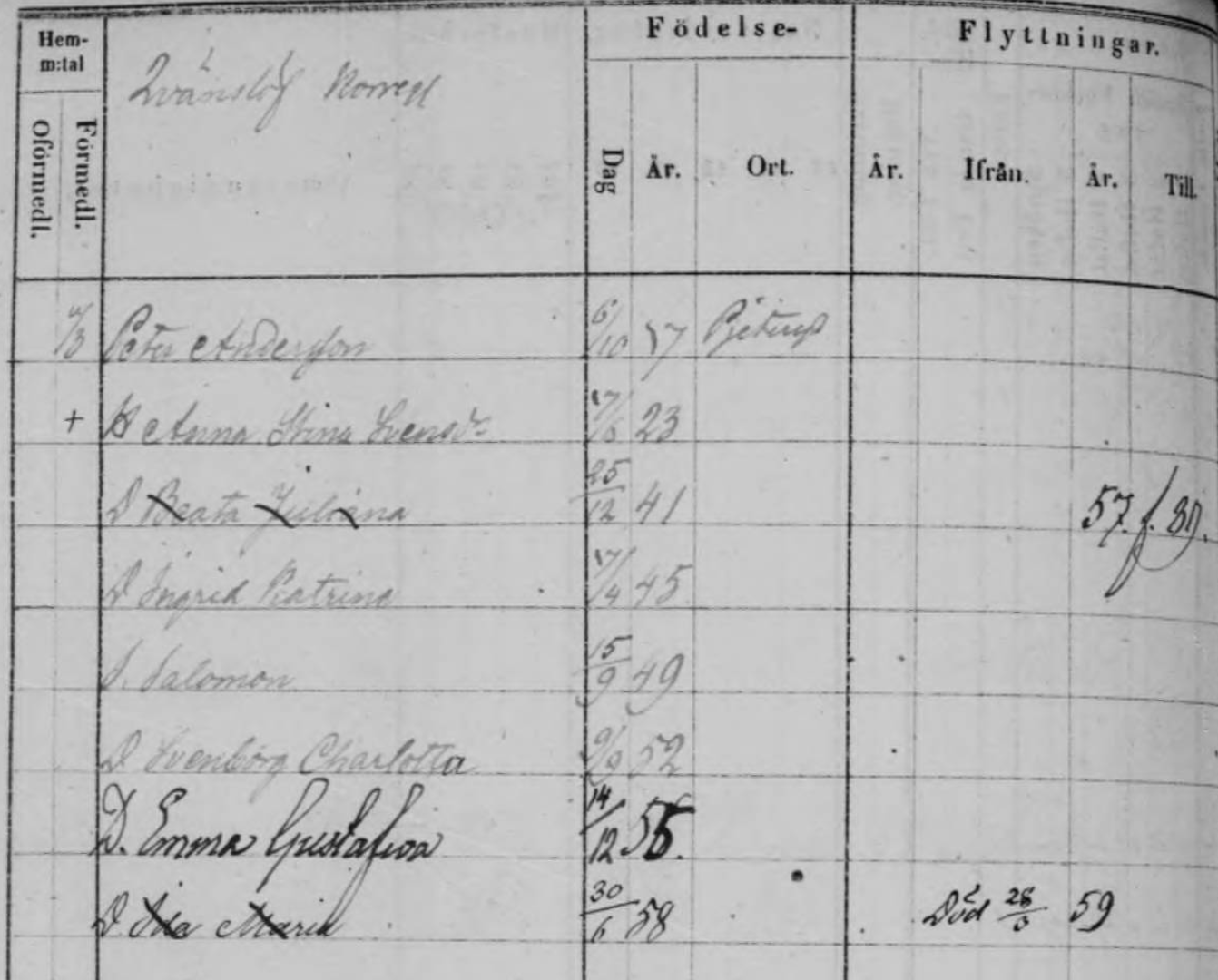

This earlier example, from the 1856-1860 book, shows Peter Andersson and Anna Stina Svensdotter (before she died) and their children. You can see in this earlier book there is a single column (Flyttningar) for comings and goings, divided into from (ifrån) and to (till). Their daughter Beata left in 1857, but stayed in the same parish: she would be found on page 89.

These earlier records also recorded deaths in the Flyttningar column: their daughter Ida Maria died on March 26, 1859.

The ifrån column is left blank for the family, indicating they didn’t come from anywhere: they would be found in the same parish, in the same village of Qvanslof Norregard, in the previous book.

By contrast, the below example shows how the page columns looked in some later books, when the ‘coming from’ and the ‘going to’ columns were divided up. Here is that same page from earlier, showing Peter Andersson with both of his wives. You’ll see that in the ‘coming from’ column, there was a note listed for Lena Cajsa. It notes she came from page 98 on May 3, 1863 - the same day she married Peter. If we turn to page 98 in this book, it indeed shows Lena Cajsa, living with her parents.

Then we have to ‘going to’ column completely separate, which is on the adjoining page all the way to the right (pictured below). It shows that the family all left for Noramerika on October 12, 1867. If they had left for a different village/farm within the same parish, it would have shown the page number, and if they had left for a different parish, it would have noted the parish place.

The example also shows something interesting in the special notes Fräjd och särskilda anteckningar column: it says “betyg till Danmark” and the date is a few months earlier than the date in the Flytatt column. This references a certificate was given to Peter for temporary work in Denmark, just a few months before the family permanently left the parish for North America - perhaps to earn the money for travel. Little details like this are what make the Swedish Household Examination Records so amazing!

The coming and going columns are by far the most exciting aspect of the Household Examination Records, but can also be the messiest to research. Although each page was a record of a period of five years, if your ancestor moved within that period there will be a totally different record of them. For example, this means that for the Household Examination Record period of 1856-1860, you could either find one record for your ancestor (if they didn’t move at all in that period) or multiple records of them on different pages and in different books, if they moved frequently.

Questions? Leave them down below and let’s talk Swedish genealogy? And check out this video for a more visual take on how to read these records: